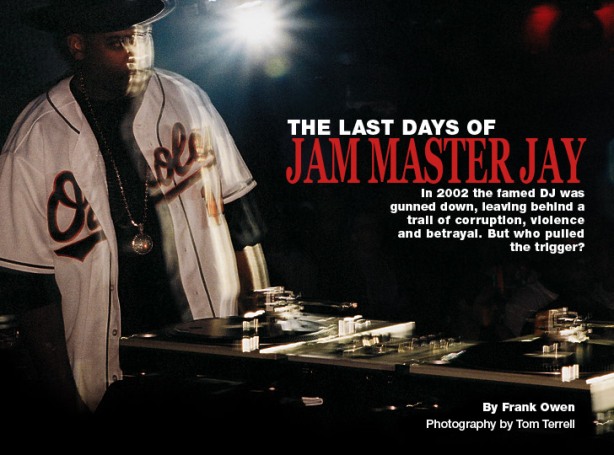

Photo illustration by James Imbrogno

Photo illustration by James Imbrogno

Baby-faced Joe is a student at an elite East Coast university who deals drugs on the side to make a bit of spare cash. It’s not a major operation: a little weed here, a little acid there. But the most sought-after item on his menu is Adderall, the popular prescription drug that family doctors and psychiatrists give to kids as young as six to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

It’s finals time, and Joe, a skinny teenager with a mop of curly hair, sits in his crowded dorm room, listening to the Velvet Underground’s paean to amphetamine psychosis “White Light/White Heat.” He and his three roommates are readying for another all-night studying session on Adderall. A book about macroeconomics sits on his desk, awaiting his attention. Joe’s cell phone buzzes. His friends have been text-messaging him all day: NEED 3 ADDY. R U AROUND. Joe texts back: COME OVER 15 MIN.

Joe (not his real name) grabs a plastic medicine container with a HIGH ABUSE POTENTIAL label on it and pours pills onto his bedspread. He separates and counts them: There are the 20-milligram standard-release tablets, which go for up to $5 each and can be crushed into a fine powder, making them popular with students who like to snort the drug to quicken its onset. Better yet, there are the orange-colored 20-milligram extended-release Adderall XRs, which also sell for $5 a pop and last up to 12 hours. Adderall XR is the Lamborghini of study drugs, the version students take when they need to drive themselves faster, longer and harder than the competition.

At 16 Joe was diagnosed as having ADHD by a psychiatrist and prescribed Adderall. Joe doubts he has a condition, certainly not one that requires a big pharmaceutical dose (60 milligrams) on a daily basis. His schoolwork noticeably improved while he was taking Adderall, but he felt hyped up all the time, like an energized zombie, as if some person other than himself were operating his body. He feared he would become dependent on the drug, and without telling his psychiatrist he stopped taking his meds. But he retained his prescription so he could sell the pills to his friends.

“My three-month prescription, if I were to sell it all, would be worth $1,500, which is a lot of money to me,” says Joe, who still takes Adderall at exam time. “I have the ideal situation for selling Adderall: I live in a dormitory with 800 other students. All my neighbors are potential buyers.”

Twenty milligrams is enough to give the user what seems like superhuman powers of concentration; it banishes distractibility and delays sleep. It can turn tedious work into fascinating material; a boring textbook can become a riveting page-turner.

“I feel like the drier the subject is, the more effective Adderall is,” says Joe. “Little details I have to go over six times when I’m straight, on Adderall they stick in my brain right away.”

Joe worries the Adderall craze on campus is getting out of control. A third of his friends use the drug. Two of his roommates also have prescriptions, one from a doctor father who knows full well his son doesn’t have ADHD yet gives it to him anyway.

“Colleges are increasingly competitive,” Joe says. “There’s an ever-increasing desire among young people to make money and become successful because that is what’s being promoted by their parents, by the university and by the culture at large. In that sense Adderall is the perfect drug for the times. I think it embodies and defines what this culture of medicating kids is all about.” He pauses. “It’s the drug of conformity. Adderall is the drug your parents want you to take.”

***

Drug use on college campuses in America has always served as a barometer of what’s going on in the culture at large. In the 1960s drugs were about the counterculture and rebellion. In the 1970s and 1980s they were about partying, sex and excess. Students in the 1990s rediscovered drugs as a source of illumination, becoming foot soldiers in the rave and neo-hippie movements. In the new millennium, however, Adderall is threatening to surpass marijuana as the most common illicit substance on some campuses. Students use it not so much to get high as for a rather prosaic purpose: to get better grades.

According to recent research done by the University of Michigan’s Sean Esteban McCabe, up to 25 percent of students at high-powered universities have used prescription stimulants like Adderall. According to the numerous interviews I conducted with students, professors and scientists for this story, use of the drug shows no sign of declining.

Adderall is a mixture of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine. It’s speed. From the 1930s to the 1970s doctor-prescribed amphetamine was a socially acceptable mainstream medicine. Every segment of American society—students, housewives, soldiers, doctors, factory workers, politicians—consumed massive amounts of amphetamine to get an extra boost for what had become known as the rat race. In the “Just Say No” era, -doctor-p-rescribed amphetamine disappeared from college campuses. Two decades later it’s back with a vengeance.

How ironic that methamphetamine continues to be demonized by the media and law enforcement as the most frightening substance since crack cocaine, while amphetamine and dextroamphetamine—different versions of the same basic drug—have once again become an intrinsic part of campus life. The major supply of speed on college campuses today comes not from scabby street chemists but from the freshly scrubbed men and women in white coats who belong to the medical establishment. Many parents who would be horrified if their children were using crystal meth are happy to see them dosed up on what is essentially the same drug, as long as it comes from a pharmaceutical company and little Jimmy or Jenny gets good grades.

Few who pop these pills have any idea of Adderall’s strange history. The drug was invented as a diet pill called Obetrol in the 1960s. It crept into the counterculture as well, including into Andy Warhol’s crowd. (Warhol had just picked up a prescription for it the day Valerie Solanas shot him at his Union Square studio.)

Obetrol’s selling point was its smooth onset. It was said to be less harsh than the more popular weight-loss pills of the time—like Desoxyn (pure methamphetamine) and Dexedrine (pure dextroamphetamine)—because of its mixture of amphetamine and dextroamphetamine salts. In the 1970s the Food and Drug Administration cracked down on doctors who prescribed amphetamine pills for weight loss. Obetrol was withdrawn from the market.

Enter Shire Pharmaceuticals, a British company at the time known less for inventing new medicines than for taking existing ones and rebranding them. Shire bought the company that owned the rights to Obetrol—as well as the factory that produced it—in 1997 and then began promoting the drug as a treatment for attention-deficit disorder.

It was a case of being in the right place at the right time. The number of kids prescribed drugs to treat ADD and ADHD in the late 1990s skyrocketed. Ritalin—which is methylphenidate, a nonamphetamine stimulant that acts in the brain like cocaine—was the most popular treatment for ADD. But after newspaper articles, and Scientologists, raised concerns about the safety of prescribing such a powerful drug to children, Adderall was aggressively marketed to physicians as a safe and longer-lasting alternative to Ritalin. By the end of 1999 Adderall had boosted Shire’s revenue to more than $400 million a year.

The moral debate over dosing children with powerful drugs continues to rage. “I don’t think there’s any question doctors overprescribe these drugs,” says William Frankenberger, a psychology professor at the University of Wisconsin at Eau Claire who has spent the past decade studying the effects of stimulant medications on academic performance. “There was a huge increase in the 1990s, thousands of percent, of children being diagnosed with ADHD and being treated with stimulant medication. Those children are now in college.”

Adderall’s popularity as a study aid really took off in 2001, when Shire introduced Adderall XR, the extended-release version of the drug. XR is a capsule containing two types of time-release beads, half of which dissolve immediately, the other half four hours later. Sales of Adderall XR grew on average 20 percent a year, and it quickly became the most widely prescribed ADHD drug in America, generating $1 billion of Shire’s $2.4 billion in revenue last year.

Although small doses used occasionally don’t result in much of a hangover, slightly higher doses extended over time can result in a harsh comedown: sweaty palms, blotchy skin, heart palpitations, strawlike hair, insomnia and limp-dick episodes. Cardiologists worry about the effects daily doses may have on the heart. In February 2005 Canadian authorities temporarily banned XR after reports of 20 deaths linked to the drug. In this country the FDA looked at the same data but concluded that the rate of fatal heart attacks among kids on Adderall was little different from the rate among those who didn’t take stimulant drugs. The feds allowed doctors to continue to prescribe it.

“Because it comes from a doctor, students don’t think it’s that risky,” says Dr. Lawrence Diller, author of Running on Ritalin and a frequent critic of doctors who overprescribe stimulant drugs to kids. “For most of them who take it occasionally in small doses, it isn’t. But a small group will overuse and get into trouble.”

Beyond the question of physical effects, what does the current campus Adderall craze say about kids these days? About the marketing power of pharmaceutical companies reaping huge profits? And the medical community, which stands between the two?

***

David (not his real name) is sitting in an exam hall, and he’s losing his mind. He thinks he’s having a panic attack. The 19-year-old economics major now realizes that washing down 75 milligrams of Adderall with eight cans of Red Bull wasn’t the best study plan he ever had. His hands shake, his mind races in a hundred different directions, and his heart feels as if it’s about to burst out of his chest. He’s pouring with sweat, and he can barely breathe. Holding up his hand, he leaves his seat and stumbles into the hallway, where after 10 minutes of drinking cup after cup of water and taking deep breaths, he’s calm enough to reenter the hall and take the exam.

“I did better on that exam than on any exam I’ve ever taken,” he later recalls. “I got a near-perfect score.”

A slightly built youth with gelled brown hair and a casual half-hipster, half-preppie style, David is a fan of Adderall. He has been taking it for about a year on a fairly regular basis, and except for that time he nearly passed out in the exam room, it has been a cool ride. “It takes away your worries,” he says of the drug. “Instead of freaking out and thinking, Oh man, I’m going to fail tomorrow, you take a pill and everything is fine.”

When I meet David, he is in the middle of finals, and in four days he has slept only eight hours. He shows no signs of tiredness. In fact, he’s feeling great thanks to the 60 milligrams of Adderall he has taken over the past 24 hours. He’s from a well-to-do suburban family, and once finals are over he’s headed to Europe for the summer and vows he won’t touch the drug for months. He says he uses Adderall mainly as a study aid, but sometimes he uses it to socialize, too.

“Adderall has added a lot to my life,” he says. “I owe a lot of my friendships to Adderall. Normally, I don’t like talking to random people, but on Adderall you’re really interested in people. It’s the get-up-and-go drug. Instead of sitting on the couch, smoking pot and watching television, I want to go out and do things.” (David has also discovered another useful role for the drug: “Jerking off on Adderall is an amazing experience.”)

When asked if Adderall has improved his grades, David pauses. “Actually,” he says, “now that I think about it, it doesn’t. My first semester I had straight A’s. The second term, when I started taking Adderall, I had straight Bs. I continued using it, and now I have an A-, B+ mix. So maybe the Adderall hasn’t helped.”

David underscores a seductive part of amphetamine’s appeal that scientists have known for decades: The substance doesn’t just give you extra energy; it makes you feel good about yourself. The drug releases in the brain high levels of the pleasure chemical dopamine, the same substance discharged while making love or smoking a cigarette. That’s why amphetamine was America’s first widely prescribed antidepressant, decades before Prozac.

A common complaint among today’s students is the constant stress and mental exhaustion they feel competing in such an academically demanding environment. The pendulum has swung away from the slacker generation, so much so in fact that one could argue college students have never before found themselves under so much pressure to perform and excel—not just to get good grades but to outdo one another. It’s not only harder to get into a good college these days (some Ivy League schools receive twice as many applications as they did a decade ago), but once you get there the pressure is unrelenting to maintain good grades so you can get a six-figure job upon graduation. The majority of students interviewed for this story expressed anxiety about disappointing their parents, some of whom are spending as much as $200,000 for a four-year degree. Adderall boosts self-esteem. It’s a drug that not only helps students manage a complex world but also makes them feel good about their place in it.

“When it costs my parents $50,000 a year to put me through college, you can bet I’m going to be stressed about getting good grades,” says David. “The reason I started taking Adderall in the first place was I thought I was going to get an F on a paper, and my father would have been pissed. My dad, who is a dentist, often says, ‘Do you know how many teeth I have to pull to put you through college for a year?’”

***

Does Adderall raise academic performance over time? This much is certain: Amphetamine medications have been used for a brain boost since the Great Depression. As far back as 1937, at a Rhode Island mental hospital, psychiatrist Charles Bradley, widely credited with discovering ADHD, dosed 30 learning-disabled children with Benzedrine (the original brand name for amphetamine) and found half the children showed “a spectacular improvement” in school performance. Bradley had accidentally found that amphetamine has the paradoxical effect of calming hyperactive kids, enabling them to better concentrate on their class work.

Within a year student test subjects in psychological studies had spread the word to their friends about amphetamine’s effectiveness as a study aid. Time magazine reported that “the use of a new powerful but poisonous brain stimulant called Benzedrine had college directors of health in dithers of worry.” One British psychologist at the time claimed “students have come to cherish this drug as a gift of the gods.”

“There’s pretty much been a 70-year use of amphetamine to help children do better in school, to concentrate and control their behavior,” says Diller. “Personally, I think Adderall has more of an effect on improving one’s sense of self than improving one’s performance.”

“I’ve been studying this for years, and I’m still not sure there’s an advantage for students taking tests on Adderall as opposed to students who study in the normal way,” says Frankenberger. “There’s good evidence that in the short term when children go on stimulant medications, the quantity and quality of their work increases. There’s no debating that. But are they learning more in the long run? The answer seems to be no.”

If it is a myth that Adderall and drugs like it are cognitive enhancers, it’s one that many scientists and researchers have taken as truth. A recent survey by Nature magazine, whose main readership works in science and academia, found roughly one in five readers used prescription drugs—including Adderall, Ritalin and Provigil—to focus concentration and increase productivity. Pilots in the military have used these drugs to stay awake and concentrate for long periods. The Adderall-on-campus issue is, in effect, the same debate that’s going on with steroids in professional sports. If the drug works, even in the short term, does taking it constitute cheating? Should all students be allowed to take it to level the playing field?

“Society is rife with hypocrisy,” says Diller. “These kids are taking these drugs for the same reason athletes are taking these drugs, the same reason their teachers are taking these drugs, the same reason businessmen are taking these drugs. It’s for performance enhancement. We live in a competitive society that demands performance at all costs and equates material acquisition with emotional and spiritual contentment. This is a culture perfect for using performance enhancers. Whether they actually work or not is another question.”

***

Susan (not her real name), 21, is a pretty blonde in a clingy black dress who goes to a well-regarded college in upstate New York. It’s summertime, and we’re sitting in a restaurant in midtown Manhattan. She describes her sorority life as being like Valley of the Dolls redux. These days there’s a drug for every occasion—OxyContin for when you want to get really zoned out, Xanax for anxiety, Valium for relaxation and Klonopin, a hypnotic drug used to treat seizures, for a pleasantly drowsy evening when there’s nothing better to do. But the crown jewel is Adderall. The drug is particularly popular among female students because, while they believe it helps with their studies, it also suppresses their appetite and helps them lose weight. After all, it was originally created as Obetrol, the diet drug. (For the same reason, Adderall has been called “the miracle pill” for Hollywood celebrities trying to control their weight.)

“There’s definitely a return to pill culture on campus,” says Susan. “I don’t know if it’s that students are more scared today to experiment with street drugs than in the past, but part of the appeal of pill culture is the feeling that these drugs are safe and legal because they come from a doctor. There’s still a lot of ecstasy and cocaine around, but increasingly, students prefer prescription drugs.”

Susan estimates well over half her sorority sisters have taken Adderall at least once. All sorts of students take the drug, she says, from straight-edge types who would never dream of taking street drugs to slackers who think they can cram a term’s worth of study into one week. On Susan’s campus little or no social stigma is attached to the drug. It’s such a normal part of campus life that students openly pop the candy-colored capsules in the library, even though Adderall is a Schedule II controlled substance, the possession of which without a prescription is technically punishable by jail time.

Says Susan, “It’s not even considered a drug anymore.”

But it is a drug, one that when taken in high doses can have some unhappy consequences. Fortunately, the students who take Adderall are usually sensible enough to take it only when they think it can help them and in small doses—usually 20 milligrams at a time, which falls well below the threshold that produces euphoria and is unlikely to cause harm.

Larger doses taken regularly over an extended time period—that’s a different story. As the legendary underground chemist Uncle Fester, who wrote the meth cook’s bible Secrets of Methamphetamine Manufacture, once told me, amphetamine “makes a great short-term friend but a lousy long-term companion.”

Playboy Magazine

Like this:

Like Loading...

According to ancient Mayan prophecies, the world will end three short years from now. Earthquakes, pestilence and revolution will bring humanity to its knees. Across the globe, thousands have already begun to prepare.“For me, being prepared for 2012 is a stress reliever. I spend an average of $200 to $300 per month on my supplies. I’ve been training myself in what I call frontier living—dehydrating, canning, preserving, cooking without modern appliances. Last weekend I started decorating our attic (almost 3,000 square feet) to store my reserve because people I know are getting suspicious of the amount of ‘hurricane’ supplies I keep. I’ll never be Martha Stewart, but I feel very good about the variety and quantity I have amassed. I believe in the three Gs of preparedness: God, guns and groceries.”—Susan Skains, Texas Gulf Coast

According to ancient Mayan prophecies, the world will end three short years from now. Earthquakes, pestilence and revolution will bring humanity to its knees. Across the globe, thousands have already begun to prepare.“For me, being prepared for 2012 is a stress reliever. I spend an average of $200 to $300 per month on my supplies. I’ve been training myself in what I call frontier living—dehydrating, canning, preserving, cooking without modern appliances. Last weekend I started decorating our attic (almost 3,000 square feet) to store my reserve because people I know are getting suspicious of the amount of ‘hurricane’ supplies I keep. I’ll never be Martha Stewart, but I feel very good about the variety and quantity I have amassed. I believe in the three Gs of preparedness: God, guns and groceries.”—Susan Skains, Texas Gulf Coast

Photo illustration by James Imbrogno

Photo illustration by James Imbrogno