Larry Levan: Paradise Lost, Vibe, November 1993

For over a decade, Larry Levan ruled the dance-music world from his roost in the DJ booth at New York’s legendary Paradise Garage. Last November, his weak heart — made weaker by years of excessive drug abuse, gave out. Was it a gradual suicide? Frank Owen looks back on the day the music died.

A TYPICAL NIGHT at the Paradise Garage began after 4 a.m. At a time when most clubgoers were finally heading home, Garage devotees were trekking through the near-deserted Soho streets. They came from New Jersey via the PATH train, from Brooklyn and Queens by subway, from uptown in cabs, and the nearby West Village on foot. They came for the atmosphere, the electricity, the “religious experience.” But mostly, they came for the music: the “garage sound” — that classic combination of booming bass, honky-tonk piano, and soaring gospel-derived vocals.

Once inside, they walked up the ramp of the old parking garage, took a right at the Crystal Room — a rest area lined with glass blocks — and headed into the main space to the dance floor. There they were met with an image both frightening and thrilling — 2,000 nearly naked figures oiled with their own sweat cavorting shamelessly with one another like a scene from a frenzied pagan ritual. Six, eight, ten hours later, these same people would emerge into the late-morning sunshine, their dilated eyes protected by sunglasses, exhausted, disheveled, but happy. The dreary everyday world seemed transformed. If only for a moment.

The Garage was, at its height in the early to mid ’80s, a veritable late-night underground pleasure palace — what with the cocaine and Ecstasy taken, the sexual acts performed, the fashionable clothes worn (not to mention the clothes not worn), as well as the seething promiscuity of the dance floor. But it was also much more: it was an expression of a collective joy that went beyond mere pleasure, a sense of shared abandon that was religious in nature and centuries old in origin. Like the pre-Christian peoples who sought to visit an otherworldly dimension through the use of drugs, chanting, flickering lights, and hypnotic, repetitive music, Garage patrons were on a quest for transcendence through music and partying, a journey that involved an excessive stimulation of the senses that promised spiritual enlightenment. “It was like an anthropologist’s wet dream,” said the late John Iozia, a Garage regular. “It was tribal and totally anti-Western.”

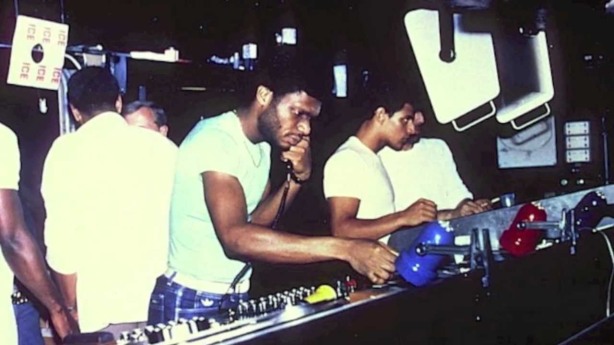

And at the center of it all was Larry Levan, the DJ/shaman — a magical figure to his scantily clad and freaky-looking followers, someone who could seemingly summon up supernatural forces on the dance floor. “He created a sense of spirituality just by playing records,” says British DJ David Piccioni, who would later work with Levan at the World nightclub in lower Manhattan.

Essential to the Levan experience was the life-affirming lyrical narrative — one that spoke of love, hope, freedom, and universal brotherhood. A narrative that he wove into the mix with songs like ‘Love Is the Message’ by MFSB, ‘We Are Family’ by Sister Sledge, ‘Someday’ by CeCe Rodgers, and ‘Let No Man Put Asunder’ by First Choice.

“He was able to get 2,000 people to feel the same emotion and peak at the same time,” says DJ David DePino, who often substituted for Levan. “He could make 2,000 people feel like one.”

One year after his death at 38, Levan is still an icon, a myth of sorts. In London, a late-blooming cult of Levan has sprouted at the Ministry of Sound, a club that has tried to replicate the Paradise Garage both physically and spiritually, with varying degrees of success. In New York, meanwhile, the deep-house scene is healthier now than it’s been since the Garage closed in September 1987. Witness the proliferation of house specialty labels such as Big Beat, Emotive, Strictly Rhythm, 111 East, and Nervous. DJs Timmy Regisford at the Shelter, Junior Vasquez at Sound Factory, Louis Vega at Sound Factory Bar, and Frankie Knuckles at the Roxy are all doing their bit to keep the spirit of the Garage alive. David Mancuso has reopened the Loft (which was the first exclusive after-hours club), and a group of former Garage employees have started a Friday-night party called the Source in an old brownstone on lower West Broadway. In the end, however, you can play the records, install the sound system, but the Garage was about a moment in time, created by the energy of a man now dead.

But Levan’s importance reached far beyond one night club and into the recording studio. A list of his mixes — ‘Heartbeat’ by Taana Gardner, ‘Weekend’ by Class Action, ‘Ain’t Nothin’ Goin’ On But the Rent’, by Gwen Guthrie, to name a few — reads like a Top 20 of some of the most innovative and important dance records of the 1980s. Though he never attained the widespread appeal and celebrity status as other DJs-turned-producers (Shep Pettibone, Cole and Clivillés), Levan’s 12-inch singles were enormously influential on the subsequent emergence of house music in the mid to late ’80s.

“Larry educated New York not just about music but about the total world of sound” says Frankie Knuckles, the New York DJ who became “the Godfather of Chicago House.” “To this day, there’s no one who can walk into a room and do what Larry did.” DJ Richard Vasquez agrees. “Larry invented new levels of bass and treble that worked on various parts of your body. He could literally make a room come alive.”

Larry Levan was a technical wizard. With Richard Long, he designed Levan speakers and installed sound systems that are used in many clubs today. He spent hour after hour testing the Garage system every week, looking for holes in the sound. On more than one occasion, with the club about to open, Levan would insist on rewiring, reconing, or repositioning speakers, making his disciples wait outside while he perfected their eventual sonic experience: bass so penetratingly loud it pulsed through your veins, combined with a crystal-clear top-end.

You could literally live at the Garage, as Levan did for the first few years of the club’s existence. All the elements needed to sustain human life were there — food, water, showers, music, friendship, dancing, sex, and later a cinema and roof garden. Most people — black, white, gay, or straight — who came were far from wealthy; some could barely afford the $10 or $15 admission. But Levan and owner Michael Brody gave them a lot for their money, even serving turkey with all the trimmings at Thanksgiving and Christmas. As David DePino puts it: “Larry and Michael came from the old school, where the party was always more important than making money.” The Garage was a world unto itself, a Utopian community cut off from the surrounding city. They dubbed it “disco heaven.”

Because of the Garage’s strict door policy, membership (which wasn’t easy to come by) was highly prized. At a prearranged time on a weekday, hopefuls would line up outside. There, a stern-faced Michael Brody would quiz them on their sexuality and why they wanted to come to his club. The so-called core membership — the predominantly gay Saturday-night members — could also attend the mainly straight Friday nights, but not vice versa. “There were straight guys who would swear to Michael that they were gay so they could get a Saturday-night membership,” Mel Cheren recalls.

A select few — Levan’s friends and music-industry folks — were given VIP cards and would clog the DJ booth on Saturdays, creating a scene within a scene. Drugs flowed freely, business deals were struck. A steady stream of celebrities — Mick Jagger, Diana Ross, Boy George, Keith Haring, Mike Tyson, Stevie Wonder — came to pay their respects to Levan.

A frequent visitor to the booth was radio jock Frankie Crocker, then the program director for WBLS, when that station was the most progressive black-music outlet in the country. Crocker would hear a left-field dance track such as Loose Joints’ ‘Is It All Over My Face’ in the wee hours of Sunday morning and have the record all over the New York airwaves the next day. “Larry was always ahead of the latest trends,” Crocker says. “He was the first person to turn me on to Madonna.”

Levan didn’t play just the R&B-flavored dance tunes — “garage music” or “deep house.” “Larry would play the latest underground cuts from Chicago, then he’d put on ‘Jump’ by Van Halen or ‘Love Is a Battlefield’ by Pat Benatar,” remembers David DePino. “People would be gagging. But eventually they accepted it. He was the bravest DJ I ever knew.”

Larry Levan had come of age during an era in New York nightlife now gone forever, a time of innocent decadence — the pre-AIDS good times, when experimentation with sex and drugs was commonplace. He refused to believe that the party would ever end.

But it did. After the Garage closed, Levan was unable to recapture the glory of the early ’80s. His drug use — cocaine and heroin mainly — his chronic lateness, and his extreme mood swings had always been notorious, but now his erratic behavior intensified. He would deejay intermittently at clubs in New York, London, and Tokyo, sometimes so stoned he’d forget to put records on. One night at Trax, Levan was found asleep in the DJ booth in a pool of his own vomit. As Mel Cheren, the Garage’s main financial backer, puts it: “Larry Levan was the king who lost his kingdom.”

LARRY LEVAN was born Lawrence Philpot on July 20, 1954, at Brooklyn Jewish Hospital, when his older brother and sister, twins, were 18. Philpot, which he would later drop, was his father’s name. His parents never married and Levan was, in effect, raised as an only child; he lived with his mother, Minnie — a dressmaker — in a rambling house in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and inherited his love of music from her. She listened, constantly, to blues, jazz, and gospel singers and taught her youngest son how to use the household record player when he was three. “I’d make him put records on so that we could dance together,” she remembers.

Levan played his first engagement at five. “It was a birthday party for a neighborhood kid,” Minnie Levan says. “He was so small they had to put the record player on a low chair so he could reach.”

As a child, Levan was an acolyte — a type of altar boy — at a local Episcopalian church. He was also a bright kid at school, excelling in math and physics, and so adept at taking apart and putting back together various mechanical gizmos that his teachers predicted he would become an inventor. Born with a congenital heart condition and prone to bad asthma attacks, Levan was a fragile boy who would sometimes faint in class. As a result, he fell behind in his work and eventually became a perpetual truant.

One day in his mid teens, walking through the neighborhood, Levan had a revelation. Hearing music coming from the window of a house, he stopped to listen, and was amazed when one song meshed seamlessly with the next. Knocking on the neighbor’s door, he introduced himself to the would-be DJ, who owned a primitive mixer. Levan became fascinated with the idea that the music should never stop. He began attending a private dance club — the Loft — and was quickly befriended by the bearded, long-haired owner and DJ David Mancuso, who encouraged Levan’s interest in stereos and lighting.

Housed in the factory loft where Mancuso lived, the club — after its inception on Valentine’s Day, 1970 — was the prototype for all the late-night dance dives that followed in its wake, including the Garage. Its basic format — members only, no alcohol, minimal decorations, and great dance music played on a clean-sounding system — was widely imitated. “I was very much into the underground thing,” says Mancuso, who has never advertised or promoted. “Maybe it was my hippie background.”

From the Loft, Levan moved on to the Gallery, and then to the famed Continental Baths where Bette Midler got her start. One night when the DJ walked out, Levan, 19, went from working lights to turntables. In the fall of 1974, he began deejaying at Soho Place, another lower-Broadway loft — this one belonging to technical whiz kid Richard Long, who would go on to build the Garage’s state-of-the-art sound system. (Long passed away in the mid ’80s.) Next came Reade St., where owner Michael Brody and Levan hatched plans to launch a much bigger venture, the Paradise Garage, in an indoor parking lot in Soho. The initial opening of the Garage, in January of 1977, “was a disaster,” recalls Mel Cheren. “The sound equipment got stuck in a blizzard at an airport in Louisville, Kentucky. And people were kept outside in 17-degree weather. Some of them never came back.” The Garage was relaunched with a string of so-called construction parties later that year, but it was not an immediate success. “The club didn’t really take on the atmosphere that people remember it for until 1980,” says Cheren.

In the meantime, Levan began doing remixes. His first was ‘C Is for Cookie’ by Cookie Monster, a disco novelty record based on a song from Sesame Street that was released in 1978. The next year he remixed Taana Gardner’s debut single ‘Work That Body’. His first big dance-floor hit was ‘I Got My Mind Made Up (You Can Get It Girl)’ by Instant Funk. The record went gold and Levan’s studio career took off. Levan’s most prolific period came in the early ’80s. Working for the cream of New York dance labels — West End, Salsoul, Sleeping Bag, 4th & Broadway — he remixed a string of records that would change dance music forever. Sublimely soulful and musically adventurous, such cuts as ‘Give Your Body Up to the Music’ by Billy Nichols, ‘Serious Sirius Space Party’ by Edna Holt, and ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’ by Jocelyn Brown showed that dance music could appeal as much to the imagination as to the body. Levan’s quintessential work came with the N.Y.C. Peech Boys, the group he cofounded and coproduced with Michael de Benedictus that featured the glorious vocals of Bernard Fowler. The group’s best-known song, ‘Don’t Make Me Wait’ — with its clap track and a cappella segment — took nearly a year to record because Levan — weekend after weekend, testing new versions at the Garage — never finished until the single was absolutely perfect.

But the same perfectionism that made him the most revered DJ in the history of club music, coupled with a rock star’s twin addictions to drugs and ego, would ultimately undo Larry Levan.

ONE NIGHT, IN 1988, barely six months after the closing of the Garage, Levan was spinning at the World in the East Village when, on a whim, he decided to play ‘ABC’ by the Jackson 5.

But the chirpy pop-soul didn’t go over too well with the hardcore dance devotees. They had come to hear the sound Levan made classic during his 11 years at the Garage. Some dancers folded their arms and stood still, staring up at the DJ booth in the balcony. Others squatted on the floor.

Enraged, Levan hurtled down the stairs, yelling and screaming, ordering people to “get up and dance.” Returning to the booth, he let the record end before putting it on again. When this drew even more protests, he played the Jackson 5 tune for a third time.

“That’s when I knew I couldn’t use him anymore,” recalls nightlife mainstay Steven Lewis, then the manager of the World. “It was no easy thing sacking the greatest DJ on the planet.”

But it had been a long time coming. The final two years of the Paradise Garage had not been Levan’s best. He confined himself largely to Fridays with its less demanding audience. His production career was in the toilet: record companies shied away because he missed sessions or fell asleep in the studio, and when he was awake, Levan took so much time with each song that the recording bills were astronomical.

Levan seemed to deliberately court trouble. He routinely spent his rent money on drugs, and one time had to go into hiding, fearing for his life, after threatening his Chinatown landlord with a loaded pistol. His relationship with Michael Brody, who had been his father figure, rapidly deteriorated. And then, when Brody was diagnosed with AIDS, it seemed inevitable that the Garage would have to close.

Says David DePino: “When Larry knew the Garage was going to close, he freaked. He went on a self-destructive binge. He took drugs to spite people, to hurt them. The more you would say, ‘Larry, please don’t do so many drugs,’ the more he would do them — right in your face.”

Veteran DJ David Mancuso sees it differently. “People made drugs available to him because it kept him in check and under their control. Larry was very frustrated. He could have grown — and he wanted to grow, but he was held back,” Manusco explains. “I talked with Larry about why he did so many drugs and he told me it was because he was lonely — spiritually lonely. He had no one to turn to who didn’t want something from him.”

MoonRoof Records owner Will Socolov, who employed Levan at his old label Sleeping Bag, puts it this way: “When you’re a genius like Larry, people cater to your every whim and allow you to do whatever you feel like doing.”

Larry Levan was encouraged to behave like a spoiled child by the people who surrounded him. First by his mother, then Michael Brody, and then, when Brody died soon after the Garage closed, the extended entourage that accompanied him everywhere — they took care of the adult responsibilities that Levan refused to deal with. One moment, he would be the most caring and generous person imaginable. The next, he would turn into an ogre. “Larry was so mean to Michael in the final days,” DePino says. “He got Michael so mad that he took him out of his will so Larry didn’t get the lights and sound system he was supposed to.”

September 26, 1987, the last night of the Paradise Garage, was a bittersweet affair. The previous night two people were killed and one was wounded while standing in line. People traveled from all over the world to attend the closing weekend. Keith Haring, whose trademark graffiti squiggles covered every available surface in the club, flew in from Tokyo.

Under the spell of Levan’s narcotic mix, people seemed to transcend human limits. Men crawled about on their hands and knees howling like dogs, while others gyrated and leapt as if they could fly.

After a 24-hour marathon, an exhausted crowd gathered in front of Levan’s DJ booth and pleaded, “Larry, please don’t go.” Standing in the middle of a dance floor littered with “Save the Garage” stickers, they dreaded a future without this “church-cum-co-operative for space-age Baptists,” as John Iozia dubbed the club.

The death of the Garage marked more than the end of a single disco — it was part of a tide change in club culture. It was around the same time that the first Todd Terry records appeared, as dance music headed in a harsher, more frenetic direction that appealed to a younger, straighter crowd.

To this new generation, weaned on more brutal sounds, Levan’s essentially integrationist message of love and peace seemed old-fashioned. And without the arena that the Garage provided, Levan’s talents seemed less special, less relevant. New York City, with its fickle tastes, had found a new soundtrack.

THE DEEJAYING tour of Japan that Levan took just before he died was the highlight of his grim last days. In the two months he was in the country, Levan was treated like a star, a living legend. Fans waited for hours outside clubs to catch a glimpse or an autograph. “We had the best time in Japan,” remembers Cheren. “It was like the old days again.”

One night, in a hotel room in Okinawa, he and Cheren had a heart-to-heart. “Promise me that I’ll live to see you back on top,” Cheren said.

“You will,” said Levan. “And this time, I won’t screw up.”

It was a promise he couldn’t keep. Near the end of the Japanese excursion, Levan fell and hurt his hip. Returning to JFK Airport in a wheelchair, he checked himself into Beth Israel Medical Center. He soon fled, claiming that people with TB were wandering the corridors without masks.

After a brief stay at his mother’s place, Levan went back to Beth Israel, complaining of a bad case of hemorrhoids. At 6:15 p.m. on Sunday, November 8, 1992, four days after Levan had been admitted to Beth Israel for a second time, Mel Cheren received a phone call from a doctor. Larry Levan, too weak to survive an operation, had died of endocarditis, an inflammation of the lining of the heart, that had been exacerbated by the massive amount of illegal pharmaceuticals he habitually snorted, smoked, swallowed, and shot up during his lifetime. Why Levan — who had known about his heart condition since childhood — continued to use drugs long after it was clear he was killing himself is a mystery. That it amounted to a gradual suicide is not. “Larry did exactly what he wanted to do, which was to destroy himself,” says Socolov. “He knew he was going to die.” Just before his trip to Japan, Levan had told his mother: “Mom, I’ve only six months left to live. I’m dying.”

He was gone in less than four.

“HIS TASTES SHAPED DANCE-CLUB MUSIC” read the headline to the obituary that appeared in The New York Times the Wednesday after his death. A more personal note was sounded at the funeral service at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. Mourner after mourner — some who had flown in from Britain and Japan — testified to the positive effects that Larry Levan had on their lives. “785 people showed up to Larry’s memorial,” says David DePino. “Of them, 150 were friends, the rest were Garage kids. He was the last DJ who could touch people that way.”

[…] Larry Levan: Paradise Lost, Vibe, November 1993 […]

The most accurate chronicle I’ve never read about him